"I was amazed by his feet. I knew later that he ran barefoot. The soles of his feet were as thick and black as coal. I remember that I wanted to touch his feet, the hard skin of which resembled the tyres of big military trucks. I was sure that he would feel nothing but, on the contrary, this hard skin was very sensitive: I hardly brushed it with my finger and he jumped up on the bed and gave me an astounded look."

Rhadi Ben Abdesselem, silver medallist at 1960 Rome

|

| The legendary Ethiopian runner Abebe Bikila, Olympic champion at the marathon in Rome 1960 and Tokyo 1964 http://blogs.diariovasco.com/airelibre/2011/11/14/abebe_bikila_cuesta_abajo/ |

One of the most memorable moments in Olympic Games history was when that Ethiopian barefoot runner entered the Roman Via Appia to produce a shock victory at the marathon in a new world record time, becoming the first ever black African Olympic champion in 1960. No one had ever heard of him and it was indeed the first international competition of 27-year-old Abebe Bikila. However, prior to the race, Swede Onni Niskanen had actually warned journalists about the chances of his trainee, stating he had ran during the year the marathon in 2:21:23, a respectable clocking, well under the actual Olympic record of Emil Zatopek. No one took him seriously. Imagine he could have added that mark had been achieved at the national trials with the hindrance of altitude and through a hilly course.

Italy Roman Empire , in a setting which has been described as a mix between gladiator games and Verdi opera. (2) The last kilometres of the track followed the ancient military route Via Appia Antica. Every ten metres there stood a uniformed soldier carrying a torch in his hand. The torch spread its flickering light over the antique ruins in the background. There was however a relic in the scene which did not belong to the age of Octavius Augustus: that monumental obelisk had been looted by the invading Mussolini troops as a trophy war in 1935 from Axum in Abyssinia .

The favourite, Russian Sergey Popov, who had broken the world best at the European championships two years before, had been left well behind. The race had become an unprecedented duel among two Africans: World Cross Country champion Moroccan Rhadi Ben Abdesselem and unknown Ethiopian Abebe Bikila. The cameraman by then was focusing in the latter runner bare feet. TheAxum obelisk, with 2000 metres to go, was precisely the symbolic place chosen by Niskanen for Bikila’s decisive attack. When that modern gladiator, “whose running was so light that his feet scarcely seem to touch the ground” (1) surged away, his last companion was unable to respond. In huge disbelief, the journalists inside the box press could hardly found appropriate words to describe this unbelievable victory: "Suddenly we could see the lights of a little convoy twinkling in the distance - here he came... trotting rhythmically and strongly up the Appian Way, the route of the conquerors in a city where his ancestors had once been slaves." (1)

In fact, Bikila’s triumph had more contemporary implications: Mussolini, in spite of sending all the best of his army and using chemical weapons, had never really got to coloniseEthiopia Africa in its historic moment of emancipation and rising. Ghana Ethiopia 15 km longer. (4) Reputed sportive journalist Robert Parienté from L’Équipe believed in athletics “there are no spontaneous generations”, but that man had come from nowhere to win an Olympic gold medal in such incredible fashion. That Ethiopian’s superhuman nature had made the miracle. Yet, was it all the truth about?

Abebe Bikila was born the 7th August 1932 in Jato, a remote village in a countryside of rolling hills of difficult access even today, about two hours North of Addis Abeba. Jato is in the Oromian region, where almost every Ethiopian runner comes from. As every one of his countrymen, Bikila’s father was a shepherd and thus the future Olympic champion grew up grazing cattle. Interestingly, Rhadi Ben Abdesselem, the runner-up in Rome , came from similar background, being also a shepherd, yet in Moroccan Rif Mountains 3000 metres high.

The favourite, Russian Sergey Popov, who had broken the world best at the European championships two years before, had been left well behind. The race had become an unprecedented duel among two Africans: World Cross Country champion Moroccan Rhadi Ben Abdesselem and unknown Ethiopian Abebe Bikila. The cameraman by then was focusing in the latter runner bare feet. The

|

| Abebe Bikila leads Rhadi at the last stages of 1960 Rome Olympic marathon http://deportesar.terra.com.ar |

In fact, Bikila’s triumph had more contemporary implications: Mussolini, in spite of sending all the best of his army and using chemical weapons, had never really got to colonise

|

| Abebe Bikila at home with her wife and daughter Tsige http://www.elgrafico.com.ar |

As he was 19 Abebe moved to Addis Abeba, following her mother. After a year unemployed, the young man was lucky enough of being engaged at the imperial bodyguard of Emperor Haile Selassie. This responsibility would be important in the development of his personality. Journalists and writers who went to meet Bikila in his home country described him as a serious and reserved man but interesting and cooperative. “His smile is slow, but when it comes, it is complete and rewarding, like the opening of a wide curtain.” (5) Bikila was fond of sports. In his youth he had played ganna, which is a sort of an Ethiopian long-distance version of hockey, with the goalposts in the opposing team villages - maybe a couple of miles apart. In Addis he enjoyed more westerner sports as volleyball, basketball and football In 1956 he started practising athletics too. He was 24 years old, not the usual age for a beginner in track and field but, as we saw before, he actually had a long experience in running. When Onni Niskanen, the national coach, knew about this man who to be fitted would run the 20km distance back and forth from Addis to Sululta every day, decided to make of him a marathon specialist.

|

| Abebe Bikila is awarded by Emperor Haile Selassie, after returning victorious from Rome Olympic Games http://www.tadias.com/07/26/2008/remembering-olympic-hero-abebe-bikila/ |

Onni Niskanen was one of the around 600 Swedish who were engaged in the development of Ethiopian society, with a blend of adventurer and humanitarian spirit. Haile Selassie I, the last of the descendants of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, was proud of being the head of a nation which had got to remain independent for centuries. Notwithstanding, Ethiopia was a backwards nation, with a big average of unemployment and whose inhabitants kept living in straw-roofed mud huts, even in the capital, Addis Abeba. The Negus wanted his country to become a modern nation but on the other side knew the danger of being dependent of the USA or the Soviet Union . Back from the exile after the end of World War II, he asked for help a neutral country, Sweden

When his contract training with the imperial bodyguards expired, Onni Niskanen was engaged by the Ministry of sports and became also the Secretary-General of the Ethiopian Red Cross. Niskanen, along with ten other compatriots, organised the practise of sport, following the Swedish model, at school, police and military level, starting from scratch. “When we arrived there was not a civilian sports federation, no organisations, no sports grounds and no instructors or leaders.” (6) Ethiopians enjoyed competitions but it took some time until they understood the need of regular training. Soon it was evident the main sport would be long distance running. In the absence of sport grounds and equipment it was the logical choice. Besides “running is a natural way of transport in Ethiopia Addis Abeba 1952 in Helsinki

|

| Major Onni Niskanen and Abebe Bikila take a break in their training session http://bildgalleri.onniniskanen.se/#1.10 |

Onni Niskanen had his native Finland in his heart and he proved it fighting for his country independence in both World Wars. As a fanatic of track and field to the point her first wife gave him an ultimatum so he had to choose between sport and her, Onni knew every exploit of the legendary Flying Finns Kolemainen, Nurmi, Ritola or Iso-Hollo. (7) However as a Swede athlete, then coach, he looked for the antidote to beat their invincible neighbours, along with other Swedish trainers, and eventually got it. The winning formula was called fartlek (speed play), which was a form of interval training with a free blend of both aerobic and anaerobic system developing strategies, speed and endurance, in a natural environment. During a fartlek session, faster-than-race pace was required. (8) This method, created by Gusta Holmer, was disclosed when Gunder Hägg trained at Gösta Olander's in Vålådalen but Niskanen was also in the same town at the time and he might have been first. (2) With their innovative workouts, Hägg and Arne Andersson would smash the records from the 1500m to the 5000m during the 1940s.

No matter he was or was not the inventor of fartlek, Niskanen introduced the Swedish “natural school” methods in Ethiopia. The coach of Abebe Bikila left precise information, later published by his heirs at the Niskanen foundation, about his training strategies prior to Rome Olympics. As in Holmer’s, fartlek in the forests was combined with track sessions, with the emphasis in speed, and long road runs up to 32km. “Cross-country running sessions of 1 to 1½ hours were part of the daily training for the long distance runners, but not some casual jogging. Pace training, pace training and more pace training. Speed running for 4-500 metres at highest speed, up rather steep slopes, varied with a bit slower running in between. The same thing when it came to track training. Pace! Six to eight 1.500 metres races, to start with in 4minutes 20 to 25, then they had to press the times downwards. They also ran on the track for 30 - 40 minutes, with varied pace. Sometime full speed through the bends, sometimes on the straights. Road running was done twice per week and on distances that were increased day by day. Sauna baths twice a week was included in the training, as well as massage after the road running.” (4) As you can guess, race pace was also required by Niskanen during the long road runs. Thus Bikila did 32km at 3:10/ 3:15 pace average. With such preparation the gold medallist in Rome

Abebe Bikila’s Olympic victories were the combination of the athlete immense talent and the wise preparation of Onni Niskanen for the event. Yet when they first met, the future champion was no more than a rough diamond: "When I started training him, he ran like a drilling soldier. A long-distance runner must concentrate on running with a minimum loss of energy." (1) However the pupil’s willingness and self-discipline brought him to improve quickly in every aspect of his technique to a flowing and relaxed style, which one day would be described as so light his feet scarcely seemed to touch the ground. Besides his discipline, focus and wish of learning, Abebe had a never seen before capacity for running. He could endure the toughest training regimens and seemingly never got tired… And behind him was a coach with the intelligence and knowledge required to guide him to the top. Even the decision of running the Olympic race barefoot was taken by Niskanen. Usually, Bikila and the second Ethiopian marathoner selected for Rome, Abebe Wakjira, would run without shoes but there was also the national pride: showing up two barefoot Ethiopians to the whole world, would result in negative image for the country; it would seem as though they were so poor they did not have the money to afford shoes for their representatives. Bikila and Wakjira were tested with and without shoes on the Olympic marathon track. Niskanen realized both runners were faster running barefoot and besides their style was more effective. The coach took the risk and asked the runners to also walk without shoes on even in the Olympic village to harden their feet. Wakjira recalls they needed to hide into the tent because athletes from other countries were laughing at them… but he who laughs last laughs longest.

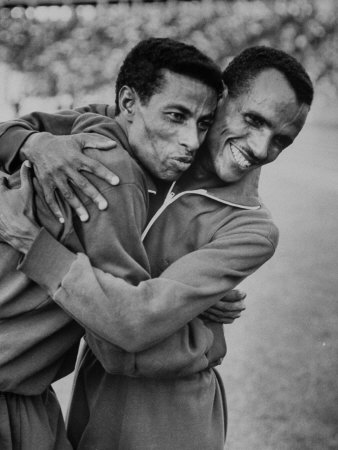

Abebe Bikila’s gigantic size as athlete overshadowed other excellent runners in the  |

| Abebe Bikila and Mamo Wolde, the first Ethiopian Olympic stars http://www.allposters.es/ |

Abebe Bikila’s 2:15:16 world record from Rome was broken by three other athletes before Tokyo Olympics: Toru Terasawa of Japan , Leonard Edelen of USA and Basil Heatley of Ireland Osaka , Kosice (9) and Boston, now wearing running shoes.

Abebe Bikila was mentally ready to defend in Mexico Ethiopia London Munich

(5) http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1077079/1/index.htm

(6) http://onniniskanen.se/eng/svenskidrott_eng.php

(6) http://onniniskanen.se/eng/svenskidrott_eng.php